|

Welcome To Iroquoia

A Review of the Literature

by

The League of the Iroquois by Lewis Henry Morgan, 1851

A Narrative of the Life of Mary Jemison by James Seaver, 1823

Skunny Wundy by Arthur C. Parker, 1926

The Death and Rebirth of the Seneca by Antony F. C. Wallace,

1969

The Reservation by Ted Williams, 1976

In their own language, they called themselves individually Ongweh

Howeh, or "real People," and as a member of the group Ho-de-no-sau-nee,

"people of the longhouse." The French missionaries and traders who first

explored their homeland in what has since become New York borrowed a word

from their longtime Algonquin enemies and called them Iroquois,

"real snakes."

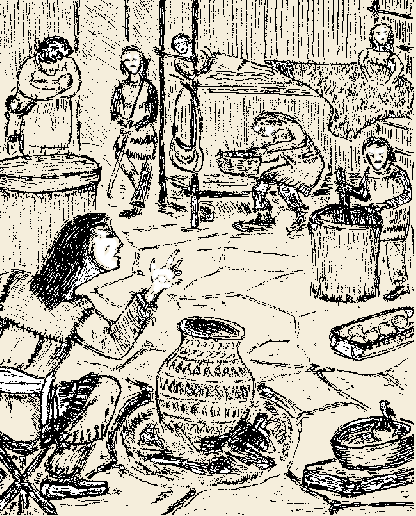

Say four hundred years ago to this winter day, the native inhabitants

of the village of Canandaigua, "place chosen for habitation," would have

been keeping themselves busy inside their bark longhouses and hunters'

shelters. A few men might be out in a hunting party looking for deer yards

or beaver lodges, but most people would have been doing a little light

work, tanning hides, stirring the stew pot, sewing and repairing equipment

and clothes, playing with the children, carving a snow snake or a spoon,

lounging on the racks of bed-shelves built over corn storage bins against

the lodge walls, gambling, eating, telling stories or sleeping. Stories

were an important feature of the long winter season when families kept

close to their fires in the bark and pole lodges. During winter months,

old people told stories to teach the youngsters and amuse themselves.

The etiquette of storytelling confined the practice to the winter months,

"when the snakes could not hear them."

Illustration by Bill Treichler

With snow making the roads slick today, I can imagine myself snowbound

here in Canandaigua, as I sit comfortably in the bay window of what was

my great-grandparents' house. Looking out the windows from the comfort

of my chair, feet up on the warm radiators, I can tell you about the time

when Main Street was a short section of the Great Trail which ran east-west

as a sort of Main Street of the League of the Iroquois. It crossed streams

at shallows, connected lake to lake, and village with village as clearings

in the vast forest.

Seneca-Cayuga-Onandaga-Oneida-Mohawk, just like that west to east. Add

the Tuscaroras in the early 1700s. They stretched across the finger Lakes—Conesus,

Hemlock, Canadice, Honeoye, Canandaigua, Seneca, Cayuga, Owasco, Skaneateles,

Otisco—and surrounded Onondaga and Oneida Lakes. The trail connected

tribes whose dress, customs and language would have been immediately and

noticeably different to the Ongweh Howeh, but who could make

themselves understood in their neighbors' territories. Among them there

were some small differences but much was the same.

In the village clearings there were longhouses, some several hundred

feet long, made of elm bark lashed over poles, with open fires inside

and smokeholes above, housing several families. The family "apartments"

were casually separated by bark, mats and hanging furs. Around the outside

of the village clearing, they may have erected a log palisade to discourage

any surprise visits. Running water was always nearby. Also around the

village were their fields and orchards: apples, plums and peaches. In

the mounded fields were the dry stalks of corn, beans and squash, harvested

and stored away months before. The villages were small centers of activity

in the forests which stretched for hundreds of unbroken miles, the only

openings made by fire, blow-downs and washouts. During the winter months

the home fires would have burned continuously but were banked low for

slow times.

The Iroquois may have provoked more literature than any other Native

American group, more books than any "discovered" people. The Iroquois

have been in fashion, out and in again, both in popular images and anthropological

study. They have been both "noble" and "dirty," have occasioned good and

bad books, accurate and inaccurate accounts, sensational novels (literary

Cooper and popular Chambers), and many collections of their goods, habits,

history, rituals and stories. Here, I'll only discuss a few outstanding

examples of the books which I like best, and I like each of them for different

reasons.

The League of the Iroquois is considered a classic as a first

study in the modern discipline of anthropology. The author, Lewis Henry

Morgan, an attorney from Aurora, New York, practicing in Rochester, became

interested in the Iroquois through fraternity ritualism and was lucky

to find an excellent guide and informant in the person of Ely Parker.

Parker, a Seneca of a distinguished family, was eager to be taught legal

practices so that he might defend tribal lands against the encroachments

of the Ogden Land Company. Morgan was a wealthy lawyer, able to help the

Seneca to a long-fought but momentary victory in retaining their lands.

Both Morgan and Parker gained by this symbiotic relationship, though there

is evidence that Parker should have received more credit for The League…

than he has. Later in life, Parker became an aide-de-camp to General Grant

during the Civil War, wrote the terms of surrender at Appomatox, and was

appointed by President Grant as the head of the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

The League of the Iroquois is a detailed account of Iroquois

life covering both significant and everyday times, necessarily selective,

without precedent, and remarkably thorough. Morgan laid much of the groundwork

for the discipline of anthropology as a scientific study of man. Major

John Wesley Powell, ethnologist, explorer of the Grand Canyon, and first

head of the Bureau of American Ethnology called The League… "The

first scientific account of an Indian tribe." The book presents a strong

account of Iroquoian social and political structure but is less complete

on arts and material culture. One need only consider the neoclassical

literature which preceded it to appreciate what a leap The League…

makes, especially in advancing the scientific analysis of a society. Morgan

was particularly excited by the matriarchal and communistic elements of

Iroquoian society; he went on to enlarge his study of these aspects of

life in societies around the world in Ancient Society.

Both Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels were impressed with Morgan's work,

made a translation into German, and used his research as the groundwork

for their own economic and social theories. It's difficult to imagine

the origins of socialist thought were in the research of a wealthy upstate

lawyer. The League… makes good winter reading, requiring both

time and patience.

Though the snow lets up, the day grows darker. The days are too short

anyway. Let's consider a lighter book informative in its own way but conversational

and humorous. Ted Williams' The Reservation belongs in every

New York State library as one of Syracuse University Press' excellent

titles on native, colonial and local history. The Reservation,

as far as it can be accomplished in a written text, reads like storytelling.

Williams should be credited for creating and sustaining this style, and

the editors deserve our thanks for maintaining the tone through publication.

Apparently, Williams didn't intend to write a book. He was taking a writing

class at SUNY Brockport while working his day job as a crane operator

at Eastman Kodak. Williams' first literary efforts were poorly received.

The stories which make up The Reservation began when his professor

advised him to write something autobiographical. To Williams' surprise,

his venture into natural speech rhythms and autobiographical prose won

the praise of not only the professor but also the class. And it won not

only the approval of the class but also an especially warm response from

the woman whom he had followed in taking the writing class. To finish

the side-story of The Reservation, Williams was encouraged by

editors at Syracuse University Press to produce more stories, had his

first book accepted before it was completed, and married the woman.

Williams' stories unfold in a leisurely, measured fashion, like listening

to the best storyteller you ever heard. You don't want to finish the book.

His stories are often a kid's-eye view of growing up on the Tuscarora

Reservation in Niagara County. One story, "Thraangkie and You-swee(t)-dad,"

is nothing more than an account of the meeting and debate between two

old Indian men, a traditionalist and a Christian. Though it could be considered

a classic example of what not to do in a story ("nothing happens"), the

story grounds itself in the heart of Iroquois culture. When I heard Williams

read and tell the story one winter night in Rochester, taking first the

part of one man and then the other as they strove to divine their relationship,

it was a moving experience. In Williams' hands, the story becomes a philosophical

mediation of considerable subtlety and feeling.

Other stories such at "Hogart" and "The Sultan" are as grotesque as anything

by Rabelais. I was drawn to the stories of Williams' father Eleazar who

healed with the traditional herbal medicines he gathered and prepared.

Williams depicts twentieth-century Native American life as well as any

of the better-known novelists such as James Welch or Scott Momaday. For

slow, savory reading through the snowy months, try The Reservation.

A Narrative of the Life of Mary Jemison is a classic of biography,

or autobiography, reprinted dozens of times since its original publication

in 1823. Mary Jemison was stolen from her family in the Wyoming Valley

in 1755 at the age of 12 by Shawnees. She was traded to the Seneca and

adopted by a family who had lost a member. She lived most of the rest

of her life among the Seneca, first in the Ohio Valley and later beside

the Genesee River, sharing work with women in the fields, sometimes suffering

from memories of her lost family, but enduring in her new life. She married

a Delaware who soon died and then a Seneca named Hiakatoo, who was both

fierce in war and kind to Mary. She raised four sons and two daughters

on a piece of land granted to her by the Seneca, losing several children

to illness and violence. Given a chance to leave the Seneca after General

Sullivan's 1779 campaign of destruction, she chose to stay because she

believed her children would fare better in Seneca society.

Mary Jemison was eighty when she told her story to James Seaver, to be

set down in A Narrative…, but her mind and memory were clear

and full of the details of Seneca life. Her enjoyment of that life resounds

through the narrative. Unfortunately, her story was tampered with, although

Seaver's introduction claims the story was "carefully taken from her own

words," it is clear that Seaver prettified her story and edited for literary

effect. The scenes of daily life among the Seneca are wonderful and nearly

unique, but the account seems at some points partial and lacking in detail

due in large part to Seaver's editorial intervention. Reading A Narrative…

you find yourself wishing that Seaver had stayed out of the way or, if

he had to intrude, he'd asked more of the right questions. I have so many

questions for this remarkable woman that I'd gladly walk to Letchworth

State Park for a talk, but A Narrative… is her only answer.

The Death and Rebirth of the Seneca was written by Anthony F.

C. Wallace in the 1950s and 60s—it's a work which could easily take

a lifetime to assemble. With his training as an anthropologist and psychiatrist,

Wallace was just the right person to study the effect of the visions of

Handsome Lake, the Seneca prophet, on Seneca culture. Handsome Lake testified

that, as he lay near death in 1799, messengers from the Creator brought

him visions and stories to be passed on to the Seneca. The Handsome Lake

religion, sometimes called "The Old Way" or "The Good Message," lives

on to this day.

Handsome Lake's teachings emphasize reform and return to traditional

Iroquois values. In 1799, Iroqouis culture was in dire need of renewal—as

a people they faced the impending theft of their lands, alcoholism, infectious

disease, and a deepening demoralization. Hemmed in by antagonistic settlers

and an alien culture, their lives fell apart, lacking a center. Handsome

Lake's Old Way offered an opportunity to re-affirm and return to traditional

values, ritual speech, songs and dances. The Old Way provided a real alternative,

previously missing from their lives, to accepting Christianity or dispersing.

Handsome Lake's message could not re-weave the cultural fabric by itself

(in fact, it was the source of considerable conflict), but it could serve

as a patch, lashing the remnants together long enough to make a plan and

to begin to find a way to the future. The Good Message, unlike the later

Northern Plains' Ghost Dance, was not aimed at undoing colonial culture's

impacts; the Good Message was an accommodation and a compromise, borrowing

freely from such Christian sects as the Society of Friends (Quakers).

Iroquois community life was badly damaged in the cultural collision, and

the Iroquois would have understood little of the colonists' notions of

freedom, individualism and liberty.

After the Revolutionary War, the Iroquois culture could have collapsed.

Parts of the tribes dispersed to the west and north, but Handsome Lake's

Good Message gave them a focus for regrouping and defending their culture,

rights and land. The Good Message is eminently practical and millennial

at once. The Death and Rebirth of the Seneca provides a deep

and understanding look at lives in great stress. Is there more we could

learn from it?

Arthur Parker was a prolific author in many genres. As a museum administrator

and educator for much of his life, he was particularly concerned that

young people learn truths about Native American life. He sensed how prejudices

were rooted in innocent lives, to quote the homely metaphor, "as the twig

is bent so grows the tree." Consequently, many of his books have a clarity

and simplicity that will appeal to young and old alike.

Three of Parker's scholarly books, Iroquois Uses of Maize and Other

Food Plants, The Code of Handsome Lake, the Seneca Prophet,

and The Constitution of the Five Nations, have been reprinted

in one volume by Syracuse University Press. Parker also wrote a history

of the Seneca Nation, many archaeological papers, a biography of Red Jacket,

The Indian How Book, (a compendium of native woodcraft), a collection

of Seneca myths and folk tales, and Skunny Wundy. Skunny

Wundy is generally intended for the youthful reader because, as Parker

explains in his "A Story About My Stories," he heard them first from his

elders at an early time in his life, growing up on the Cattaraugus Reservation.

As an important part of his education, he is eager to share them with

modern children.

Skunny Wundy is a trickster whose name translates more or less as "cross

the creek" or "better guess." As Skunny Wundy says, "I never get caught."

Most of these stories fall into the category of how-stories: how the bear

got his short tail, etc. and most are about animals. Animals are by no

means the only subjects of Iroquois tales, however, and a glimpse of the

grotesqueries of Iroquois tales can be found in Jeremiah Curtin's Seneca

Indian Myths or Joseph Bruchac's Iroquois Tales which include flying

heads, stone giants, vampires, cannibals and skeletons.

Several of Skunny Wundy's stories are mysterious, and Parker ends the

book with a spooky tale of vengeance, "The Ghost of the Great White Stag."

He also includes "The Mysterious Caves of the Jungies," one of the few

descriptions and discussions of the Iroquois "little people" anywhere

in the literature. Jungies are small and old but formed like human beings.

They lived on earth before men came. Like the animals, part of some older

creation. They are of the earth, living in cliffs, caves and grottoes.

The Creator gave them three main jobs, all related to man's use of the

land—some are "stone throwers" who make the rounded stones useful

for hammers and leave them where men may find them. Underwater jungies

guard springs and seeps, keeping them clean and flowing. "Drum dancers"

are the caretakers of fruits and other food crops. The jungies are like

men and often help men but can be powerful enemies when slighted or aroused

by some wrong. They are the guardian deities of place whose influence

many religious people have seen in traditional landscapes. As Parker intended,

these stories give a brief glimpse of the Iroquoian world, through their

children's eyes. He was convinced that we would be changed by what we

see.

I have left out a great deal in what's selected and noted here. In choosing

these five books as examples, I haven't mentioned some of the great names

in Iroquoian scholarship: Fenton, Trigger, Paul Wallace, Beauchamp, Jesse

Cornplanter, Curtin, Graymont and Tooker. Writing the lives of a people

properly, could take a book as large as the land itself. Most of the books

chosen illustrate a past time and a changed world. Instead of village

clearings in a vast forest, most of the modern Iroquois live in isolated

reserves or in the midst of great cities. Who knows how long or well they

will preserve their unique identities? Who knows what has been lost already?

The feeling of their impending disappearance is nothing new, however,

and has been proved generally untrue—their culture is still here

among us, available to those who want to learn.

|