|

My Wallet of Receipts

An Exploration into how the Barter System

worked in Upstate New York

during the Nineteenth Century

by

Gary Lehmann

There comes a time in the on-going life of every family when a household

must be cleared out to make room for new life. This past summer, I spent

many long days hauling out bags of old clothes and newspapers in twined-up

bundles. Grandma and her line were prodigious hoarders, but as frequently

happens in this sort of adventure, more than a few interesting objects

popped to the surface.

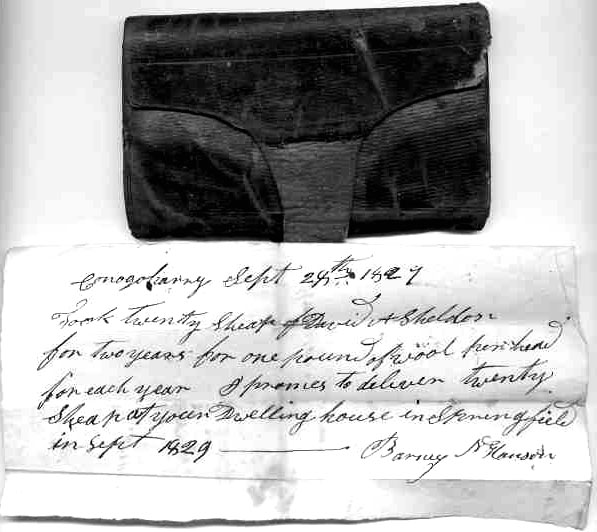

Chief amongst these treasures was a small leather wallet which was used

by an ancestor named David A. Sheldon to record business transactions

made between 1825 and 1842 in and around Richfield Springs, Cooperstown,

and Springfield Center, New York. Family records indicate that Sheldon

married a Bigelow daughter and thus became part of the family tree about

1825.

The wallet, which measures 3x5 inches, is made of fine leather folded

over several times to create a number of sewn pockets to enclose small

scraps of paper that record transactions for the purchase or sale of Indian

meal, corn, wheat, sheep, flour, stove pipe, shoe leather, apples, pork,

veal, potatoes, oats, flax seed, hay, cider, and rough stone. When a debit

or credit was satisfied, Sheldon put a big "X" over the annotation.

What becomes clear reading through these receipts is how very complex

a commercial transaction becomes before the time when the U.S. government

guaranteed the value of paper currency. Without reliable paper money,

the community largely had to transact business in other ways. Until reading

this wallet of receipts, it never dawned on me how complex that barter

system had to become to keep up. For example, grain goes bad relatively

quickly. If you can't eat it or feed it to your animals, you need to convert

it to flour or sell it right away. Fresh cider doesn't last but a few

weeks, but it can be converted to a future asset if you can get it to

your neighbors in time.

At the simplest level, goods are traded for goods, and a paper receipt

records the transaction. Sometimes, goods or services are paid for in

gold or silver coins or bullion. That is why even simple 19th century

farmers had what we call jeweler's scales in their homes. One of these

came to light from grandma's house. As an example of a "simple" transaction,

Sheldon has a receipt in his wallet that records the payment of ten dollars

from his father-in-law who he apparently successfully sued for this sum

in 1836. Bigelow paid in cash.

More often than not, a trade turned out uneven. One person offered goods

valued at more than the other had to give at that time. To resolve the

difference, a credit memo was recorded on the back of one receipt and

a debit memo on the back of the other. In the absence of reliable paper

money, which was not available until 1857, IOUs were exchanged to balance

out the transaction.

Sometimes a third hand records accepting that debit or credit as part

of a later trade. Thus, Sheldon paid a firm by the name of Stowell & Story

in Cooperstown the sum of $75.43 on James Cordell's behalf. In so doing,

Sheldon either discharged his debt to Cordell or created a new debt which

Cordell would have to discharge later on in some similar way. In effect,

the members of this small agricultural community are creating their own

paper currency in the form of what we might call commercial paper.

The total number of names that appear in this wallet of receipts does

not exceed thirty over a period of 16 years. We know from census records

that the entire community was much larger than that. So it must be that

the circle of trusted people was not as large as the population of the

entire community. There probably were people, even whole families, in

this community who had earned a position outside of this system of mutual

trust, but within the trusted members of the community, these little notes

made trades easier and quicker.

You stood to lose out on a lot of trading if you had to have your bushels

of wheat ready to trade at the exact same time and precisely the same

value as my bushels of corn. How much easier it was to hand over the goods

when they were fresh and ready and then even up the score when the other

person was in a position to reciprocate.

Thus, Delos [Delores?] Lothrip [Lathrop?] paid Robert Ormston the sum

of $1 in cash for a debt he held against Pamelia [Pamela?] Sheldon on

Dec 16th, 1825. Mrs. Sheldon received a receipt from Ormston indicating

that her debt to him was paid. The third party nature of the transaction

makes the whole economic system much more flexible. On June 17th, 1830

David Sheldon paid $30 to Joseph Stocking to settle the debt of a third

party.

In March of 1840, David Sheldon, shy of ready cash, paid his hired hand,

Th. S. Wilkins his wages for the past six months in a note which he could

use to buy goods and services anywhere in the community as long as Sheldon

was generally perceived to be a good credit risk. On May 8th, 1828, Sheldon

wrote out what amounts to a bearer bond or check to the order of an unnamed

party. "Sir please to pay the bearer three dollars and fifty cents on

my account." The bearer, perhaps a visitor to the community, now had paper

which he could use to buy things within the community.

Similarly Sheldon could go to the store and buy a bonnet and some red

ribbon for his wife and pay for it with some money, a couple of straw

hats and a pair of woolen socks, all goods which could be recycled from

the store shelves. As it happened, the transaction was uneven, and so

on the back of the receipt Sheldon indicated the extent of his further

indebtedness.

Sometimes, the signatures of witnesses appear at the bottom of a transaction

receipt, perhaps indicating that some mistrust existed between the parties

and they had to employ witnesses to avoid further controversy concerning

the payment.

Sometimes, no money is involved. On September 14th, 1827, Sheldon lent

the use of twenty "sheap" to Barney N. Windsor for two years after which

he had to return twenty "sheap" together with forty pounds of wool, rent.

All the rest of the wool Windsor might gather from tending the sheep for

two years would be his own. If I understand this system correctly then,

Sheldon might even sell a future interest in his sheep right now, based

on the paper indebtedness he held on them, even though they might not

be delivered until September 1829 at his "dwelling house in Springfield."

This paper currency makes a commodities market out of local farming.

At one point, David A. Sheldon receives a piece of paper in exchange

for the discharge of a will which calls for Sheldon to receive twenty-six

pounds, one shilling from the estate of David Little, deceased. It surprised

me at first to find receipts dated this late denominated in English currency,

but in a barter system what difference does it make? The form of establishing

value really doesn't matter as long as the exchange rate is steady. The

price of something is just a benchmark of value.

What David A. Sheldon's wallet of receipts shows me is that a community

can get along economically without very much hard currency if trust exists

between the members. In this period there were no bank regulations. Thus,

anyone could start a bank and in effect say to the public. "Look, I have

a building I have labeled as a bank. Bring me your gold and silver and

I will give you paper which says I have your money on deposit. Of course,

if someone robs the bank, your money is gone. I can't give you what I

no longer have."

All too often it was the banker himself who stole money from the vault

to make his own expenses. At that point, to be fair, he just redeemed

his bank notes at a percentage of their face value, so there would be

enough to go around. The public had no assurances that they would get

back anywhere near the money they put in. Clearly, barter, together with

the addition of commercial paper within a circle of trusted friends was

a much more reliable way to do business.

Of course, the system did fail from time to time. Sheldon had to take

his own father-in-law to court to get satisfaction, but that happens even

today when the value of our currency is guaranteed by the "good faith

and credit of the United States government." Some things never change.

© 2003, Gary Lehmann

|